Michelangelo Severgnini and Colin Clark on African Migrants in Libya!

Hello, and welcome to the second episode of art and inclusion from the Quantization podcast. I’m Kaveh Ashourinia, and in this episode, we are talking to Michelangelo Severgnini, Italian filmmaker, musician and radio producer. Colin Clark is hosting this episode.

Arezoo: Nine years after the fall of Gaddafi’s regime in Libya, as the consequence of the wake of the Arab Spring protests, Libya is still dealing with civil war. The country is divided into different parts, and regional and global players are influencing the crisis. Libya is dealing with many difficulties, but people of the region are suffering the most. The Libyan geological situation is a spot for a more complicated story, which is the massive number of African migrants trapped in Libya. They once moved there hoping for a better income in a more stable Libyan economy, or as a departure port to the European countries. Many of them are facing severe difficulties, including being tortured and dealing with smugglers and criminals.

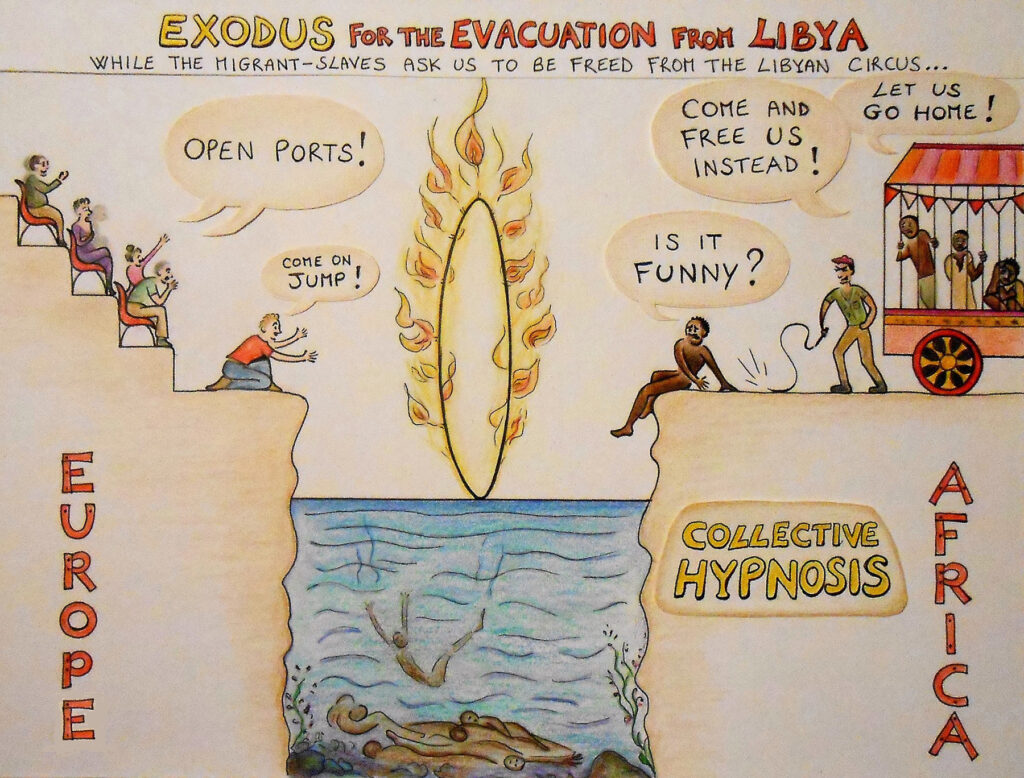

Arezoo: In this episode, we invited Michelangelo to talk about the situation. He is working on an ongoing project for over two years now and documenting these African migrants’ pains and agonies. He frequently travelled to the region to complete his documentary, Exodus – escape from Libya, and he is in close contact with many of those migrants. He is sharing his personal experience with this humanitarian crisis. He discussed the tools and somehow unique approach he used telling the story.

We also asked him about his artistic journey up to today and his life experience in various countries, including Turkey, as one of the players in the Libyan crisis. What was the motivation that prompted him to start this project, and what are the next steps?

[Short Music]

Kaveh: This is episode 13, art and Inclusion Volume 2, Trapped in Libya

[Music: Main Theme]

Kaveh: Welcome, Colin and Michelangelo, please start with your introduction.

Colin: Hi, I’m Colin Clark, I’m the associate director of the Inclusive Design Research Center at OCAD University in Toronto. And these days I’m continuing to hide out in my basement of my house, my basement studio and to work and I’m lucky enough to have been invited by Kaveh to co-host this series on the intersection between inclusion and creativity in the art. Let’s say, I’m an artist myself. I do experimental and computational video artwork, particularly looking at modes of temporality and perception in regard to video and how technology modulates those kinds of things. Michelangelo, I’m excited to have the opportunity to talk with you again.

But maybe you could start by introducing yourself and telling us all about what you’re working on these days.

Michelangelo: I’m very happy to be here with you. I’ve been a filmmaker since 15 years now. I started at the beginning especially making documentaries for the Italian TV. This happened for a few years, but after that I prefer continue as independent filmmaker. Exactly in 2008, this made for me leave my country. Also, I spent 10 years abroad making independent documentaries. At the same time, I like to say that I’m also a musician. I try to combine both things. I try to be busy with these two passions of mine. Nowadays or I can say since a couple of years, I’m focusing on the situation in Libya after I moved back to my country.

Colin: Let’s go straight into that because it seems to me that this has become an overriding passion and focus for you these days. Tell me about the documentaries you’ve made and are working on and what’s driven you to be so focused on Libya and the situation there.

Michelangelo: After I decided to move back to my country, I realized that things have changed of course in these last 10 years and especially regarding immigration because the numbers of the migrants from Africa to Europe therefore we can say mostly to Italy, especially after 2011 increased a lot. In 2015, 16, 17, were really huge numbers. Also, the methods through which the migrants used to cross or to try to cross the Mediterranean Sea changed in the last years because since five, six years now we can say the African migrants from Libya are trying to cross the sea with rubber boats. This means that these things are not able, are not capable to reach along the Italian coast and if no rescue ships or any other cargo ships for example find them in the sea, they suddenly sink after they cover neither half of the distance.

Michelangelo: Therefore, I mean, they were something already clear from the first dialogues I had with the African migrants that were just landed in Italy, that things have changed a lot. So, I had this big curiosity and then in a way I found, by chance I can say, a way to get in touch with all those who connect to the internet from the Libyan soil. That is why once I had in my hands this important tool, I thought that this had to be the things for me to do. So, now we can say we are just before our final target because the documentary you were mentioning about is basically ready. So, I’m hopeful that I could transfer whole this experience two years long in this documentary movie.

Colin: You said you’ve been talking with these migrants and it was mostly by chance that you had the opportunity to reach out to them. Tell me the background if that. How did you?

Michelangelo: Because when I was living abroad I was trying to follow of course the news about my country from the internet and it was even too easy for me to realize that all the reportage they made from Libya, from the Libyan soil we’re not particularly satisfied about them because it was clear that they were escorted. The journalists were escorted by the Libyan police and they could not exactly move freely in the country. Even when they said they were making record cash from inside the detention centers, it was clear that they were in the detention centers just beside the Libyan police. So, it was really almost impossible, basically impossible to get a real picture of the country.

Michelangelo: So, that’s why instead of reading the record cash, I preferred to ask the African migrants that were just landed in Italy and this happened in 2017, 18, let’s say. In fact, it was surprising what came out from their stories because for the first time I heard in my life that in Libya they were largely practicing slavery and also torture for ransom. So, this was shockful because in fact, no media was talking about it. At the same time, it was shockful what they were telling me and it was shockful that nobody was talking about it. At the beginning I was quite confused because how to know exactly what is happening in Libya.

Michelangelo: I just tried to find a way to get in touch with somebody in Libya and that’s why I’m saying by chance I found a method based on geo-localization that allows me to get in touch with all those who access to the internet from the Libyan soil. At that point I could receive hundreds of direct stories which were not only talking about something that happened before, like in the case of the migrants you can interview in Italy, but they were telling me their own stories while it was happening. Some of them even could find a way to access to the internet from the detention centers which is something that for me at the beginning was really impossible to believe because if you are in a prison, how can you have access to internet and chat with me?

Michelangelo: At the beginning, I was not believing it, but we had to understand that the reality in Libya is so different, is so particular that some strange things can happen and in a way luckily we can let them speak if we want. Because the most important thing of this work is that I could prove that the migrants themselves from Libya can represent their own voice. They can be the protagonist of the self storytelling and that should be important.

Colin: Yeah. This question of who’s telling a story and what those stories are is really important to me, but I wonder if before we talk about that there’s maybe some context with some background that you can share with us. Why were African migrants going to Libya and are they still going to Libya? Then what’s the relationship between migrants coming then from Libya to Italy and to the rest of Europe? Can you talk about how this connects with Europe’s fraud relationship with migrants and the racism that comes along with this kind of global crisis?

Michelangelo: Sure. I will try to make it short. Of course, me as an Italian, I used to know a little about Libya because it’s kind of a neighbor country for us. So, I have to say that things started to change after Gaddafi fell because until the point of course, for 10 years at least there were migrants trying to cross the sea. In those times they were crossing thanks to wooden boats. They were fisherman boats, so they were perfectly able to reach the Italian coast and they were just a few thousand a year. After the fall of Gaddafi things changed especially in the area of Tripoli, of the capital which is in the northwest of the country on the sea. The area was under the control of militia. Army groups that started operating after the fall of Gaddafi.

Michelangelo: This started a system of exploitation of the African migrants. We have to think that when Gaddafi was still alive, Libya was one of the richest countries in Africa in those times. So, many migrants from Sub-Saharan countries were going to Libya just to work for a couple of years, three, four years and some of them they were coming back with some money in their pockets and got something in their own countries. But after Gaddafi died, the militias started a business on the migrants, thanks also to the African mafias.

Michelangelo: Basically, the African mafias and the Libyans invested on the dreams of young African guys and girls to invite them to cross to Italy. Most of the time it was just a false promise because once they entered in Libya, they found themselves sold as slaves and many of them they were tortured for extortion. Of course, it’s very difficult to know how many migrants indeed passed through slavery, passed through torture, but for example there are some researches made in Europe interviewing those who could cross the sea and these researches say that at least 80% of the migrants that passed through Libya passed also through slavery and torture for extortion.

Michelangelo: So, we have to understand that this is because of the system and I have to say that most of the time the European media are still not ready to understand the full picture of what is happening in Libya because they just assume that Libya is a bad country from which to run away, but they don’t understand the system which is at the base of these exploitation. Thanks to which, we can today’s say that Libya has become a free zone of exploitation of the black African.

Colin: What’s the state in Libya in terms of the rule of law and the role that the militias play? I think when we talked earlier you mentioned that there was significant regional power amongst militias and warlords. How do they figure into this?

Michelangelo: Nowadays we have a government and Tripoli is still the capital of Libya. This government was formed in 2015, but in a way not all the Libyans recognize this government because after the elections, the parties could not form a majority. So, they organized… After months they organized an international meeting in Morocco, in a place called Skhirat and from these international meetings sponsored by the United Nations, they decided that Sarraj would have been the Prime Minister.

Michelangelo: The first mission of this government had to be to unify the country, but after five years, this mission has failed. It’s failed completely because now we have two parts of Libya. The one in Tripoli which is anyway in the hands of militias. Militias were supporting the Prime Minister and Prime Minister let’s say is hiding the black market and all the things that the militias are doing on the ground to exploit more the migrants and the Libyans themselves. On the east side of Libya and in the south of Libya, there is the Libyan National Army which is what remains of the old Libyan Army which now recognize itself and a second parliament which is based now in the east of the country.

Michelangelo: After almost one year of war on the ground, the Libyan National Army was about to take Tripoli, the capital, last January and to end the war, but the international community decided for a cease fire. But I have to say that in these three, four months of cease fire were used by Turkey to transfer more and more soldiers from Turkey to Libya, including more than 15000 Syrian mercenaries. Not useful anymore for the war in Syria were transferred by Turkey and employed on the Libyan war scenario and now not only Tripoli is well protected, but the Turkish army took a significant part of the country and now they are heading to the east of the country. In this same hours, in this same day, they are fighting an important battle in the city of Sirte, in the center of Libya.

Colin: I think you answered it. It was really about the role of militias and the local warlords in terms of creating an environment or a climate where there was lack of rule of law. Where the role of the police and the military was often directly less of supporting this modern day slave trade. Am I reading that right?

Michelangelo: Yeah, exactly. We have some international investigations that provide us some important points to understand. But at the same time I have to say that I have to say that even listening to hundreds of migrants in Libya and also speaking with the Libyans in Libya in these last two years allowed me to complete the picture in a way. So, as I said, I think we can say the historical mission of the militias was to smuggle the Libyan oil because they got the main support from Europe and from Turkey to be able to do whatever they want on the ground and nobody protested.

Michelangelo: In the last five years, they imposed their power with weapons on the ground and so even the political charges had to in a way obey to the will of the militias. We can say that Sarraj government served to cover, to act as an umbrella for these militias because then he comes to Rome. He goes to Paris, to London, to Berlin, and we think he’s the Prime Minister of Libya, no. He’s Prime Minister of Tripoli which is the capital, but he’s still not of the whole country. By the way, we don’t know what his or militias are doing on the ground because nobody is able to tell the story except those who are nowadays in Libya and can tell us through the internet.

Michelangelo: By the way, of course it’s a risky job. So, I careful protect always the identity of those who speak with me, but for example they provide pictures, videos. We have enough proof to say what we are saying nowadays. So, the chief of the national oil corporation which is the public institution in Libya in charge to take care of the sale of the Libyan oil, one year ago stated that around 40% of the Libyan oil has been smuggled by the militia in the last years which is of course a huge amount of money. Something like 350 billion dollars per year. This means that the impunity that the militias are enjoying on the ground primarily to smuggle this oil because there is no authority above them that can stop this trade.

Michelangelo: Who are those who are enjoying this smuggling? Exactly Europe and Turkey. We are already investigations. They already reported that things are… These things are already proved. Some people already are in jail for this smuggling. Of course the smuggling is involving also the mafia both in Malta and in Sicily. Still, the scandal is not big enough because those who are convicted until now were just little fished, let’s say. But at the same time, we know from the Chief of NOC in Libya that 40% of the Libyan oil has been smuggled. So, where is gone? So, that’s the question. It shouldn’t follow the same channel to Europe and to Turkey.

Michelangelo: Once the militias enjoy this impunity of the ground, they thought to get some more money even through the exploitation of the migrants because at that point nobody could stop them and so they thought to exploit migrants through slavery which is unpaid for labor. It means people who work and at the end they are not paid. So, they work without salary and the other is the torture for extortion which can seem something really not describable, but which is quite common thing in Libya. So, it means that the migrants are in the hands of bandits or militias. The militia torture the migrants while calling the family of the migrant back at their place and they make them hear the voices screaming of the son or daughter and they say, “Look we are torturing your son. If you will not send money, we will torture him to death.”

Michelangelo: Normally they ask four, five thousand dollars. Not so much, but for African families, sometimes it’s really hard to cover these expenses. Then we have to say because we are in Europe, we still think that Libya is a place of transit for migrants. But it’s not like that anymore because the UNHCR says that around 700000 African Migrants are currently in Libya. But in the last year, only 5000 could reach Europe through the sea. So, it means that one every 140 migrants. So, we have to start thinking of Libya not as a place of transit, but as open prison where migrants are trapped since years.

Michelangelo: In fact, it’s important to note that the last two years, it really seems that those who decided to enter Libya, the number decreased because in the African countries, now it became famous that Libya is not a place to be. That’s thanks to the 10000 of migrants from Libya decided to go home and to be repatriated. Once home, back home, they started associations to inform the young guys that if they want to migrate anywhere, but Libya.

Colin: It sounds like word has gotten out that Libya is not the traffickers claimed it would be for people and yet we’ve got more 700000 people who had traveled to Libya who are now imprisoned or are slaved there. Going back to something we talked about a little bit earlier. Having seen a little bit of your work and read some of your writing, one of the things I’m struck by and you alluded to this is the role that letting… People themselves tell their own stories. So, I hear in the documentaries I’ve seen of yours less in the way of things like overarching, there are person narrative or voiceover and instead you dive right in to letting people who have experienced this to tell their stories.

Colin: I’m putting in a position where you now have to represent other people’s stories, but can you talk through some of what of heard about what life is like in these prison camps or in other cases and what going through torture was like for these people and then what you’ve done maybe creatively as a film maker to make those voices real and direct?

Michelangelo: Yeah. In fact, you know in a way to was an interesting experience to try to figure out a place through the voice messages that I was receiving because sometimes as I said, it was really difficult to imagine what they were talking about. We were mentioning about the fact that most of them they had access to the internet from the detention center. So, how can we explain this? So, of course I ask them many times. They said, “Look, this is not a normal prison. It’s not a state prison. It’s just a compound, big place where they used to stuff migrants as they are animals. In the chaos, it’s even easy to sneak a telephone.”

Michelangelo: At a certain point, they even don’t mind because there’s nowhere you can go anyway and there is nobody who can save you because as I said, the controller of the territory is militarily in the hands of the militias. For example, the Interpol which is the International Police of Europe already has a list of tens of criminals and human traffickers in Libya, but in the last years they could not touch one of them. Still, in Europe they say that they should push, they should convince the government and then the Libyan police to work better, but for those who understand how the situation really works in Libya, it’s easy to understand that these criminals will be never caught by any police because they are the real authority in Libya.

Michelangelo: So, the day when the government will arrest one of them, that will be the last day of the same government. So, we have to imagine of Libya like South American drug cartel in a way which is also a state and which is recognized internationally as a state. So, it was an interesting experience to listen to a reality which is very far. It was sometimes scary because it was not always possible to believe all the stories they were talking about at the beginning. But after they could manage to send videos or pictures, well, I had to acknowledge that they were saying the truth. How they could send videos, just because sometimes these criminals, these legal criminals feel so confident of what they’re doing and they feel so protected that they even start shooting the torturers.

Michelangelo: When they make videos, they share the videos to each other and some of these videos reach the phones of the migrants somehow, someway, and so the migrants send to me. We have many, many videos of tortures and especially listening to the dialogues while the torture is happening, you understand what’s going on in the scene because it’s always difficult to find the reason why somebody should have been tortured, right? But when you listen to the Libyan criminal which is repeating, “When are you sending the money? Send the money. If you don’t send the money, I will not stop.” The guy answering, “Okay. Now I call my family. I swear they will send the money. I swear.” Then you understand what system is behind.

Colin: Yeah. Speaking of this kind of confidence, did you ever find yourself doubting what you were doing especially what kind of risk you might be placing the migrants themselves in by telling you their stories or how did you address that?

Michelangelo: I moved very slowly especially at the beginning about it. I never revealed any identity of those who spoke with me, but at the same time for the things they were saying and even for some noise, background noise, it was clear it was from Libya on one side. But at the same time I have to say that I’m in touch them. So, through the geo-localization, they only show thing 100% is that they are talking from Libya. But at the same time it was hard to make the people here in Europe believe what they were saying. That’s why slowly we managed to get also photos and videos. So, it took a while, especially at the beginning to understand what was the mechanism and what were the risks they could run.

Michelangelo: Then, I’ve been always extremely careful to protect their identity or for the people they spoke. For example in some cases of course we published video just by blurring the face of the people, but for the record it was clear they were in Libya.

Colin: Was it technologies that we’re familiar with like WhatsApp of things like that that you were using to reach out to these migrants?

Michelangelo: Yeah, all the social media that the whole world knows, the same are used by the migrants in Libya. This is amazing. Of course two years ago before coming this way, I could not imagine that the majority of the migrants in Libya could have access to the internet, but in fact it is like this. So, not only those in detention centers, but those who are outside normally easily can manage to have a mobile phone and they are young people. As all the young people in the world, of course they don’t come from another world. They belong to this world, so sometimes I have to say they are able to use the social media even better than the Europeans because for them it’s a matter of life.

Michelangelo: To be connected to the social, it means to know what’s happening around, to be in touch with the family, to be in touch with their friends who are also in Libya, but in another place. So, to share information and that’s why this network developed a lot in the migrant community in Libya.

Colin: Can you paint a picture of what daily life in one of these detention centers is like based on the stories you heard?

Michelangelo: In the detention centers, like is in a way always the same because there’s not even enough place to lay down on the floor. So, they are stuffed one over the other and they used to feed them, but just a little bit. Just enough water to survive and then of course it depends because even in the media internationally used to divide the so called official detention centers and the unofficial detention centers. So, the official detention centers normally should be followed by the institutions of Tripoli, but even in these cases we know that for example some policemen or I don’t know if we should call them policemen or simply criminals. They used to practice the torture even in the official detention centers or they sell people to others because the real human traffickers are outside.

Michelangelo: So, they used to come back to the detention centers and to buy people from the detention centers. Why? If they are in the unofficial detention centers, then, over there is very critical because maybe they will not even stay for a long time or the family sends money and so they are released or they are killed, basically killed. But for the rest, they just stay there and waiting for something to happen, but nothing happens all the day. So, they are just there, one over the other and of course it’s also psychologically very difficult. Many times they told me about stories of people who simply could not bear the situation and more so they started shouting and they started losing control.

Michelangelo: So, we have to think that all of these people now are in these conditions since a few years. So, now it’s mentally very difficult for them to continue in this situation.

Colin: Did you hear a sense of hope or anything to keep people going? Any stories?

Michelangelo: Actually not. Those really hopeful, I could speak with were those who finally decided to go home. Even for them it is not easy because those who want to go home are more than the places on the flights that the IOM (International Organization for Migration) is providing for voluntary repatriation. So, it means in the last three years, around 60000 people were repatriated through flights from Tripoli to the main capitals of the African countries. It happened many times to follow the stories of those who were going back. I remember when I could speak with them just a couple of days before the flights. They were extremely happy to leave that hell.

Michelangelo: But for all the others, those who for example they cannot go home because they come from Somalia or some other countries where there is war, so they have no alternative. For them it’s very difficult to have hope. It’s true that the UNHCR managed to evacuate 2000 of them. Some direct to Europe, some temporarily to Niger and also to Rwanda. Just to find a place, whatever place out of Libya that would be good enough for those people just to escape from Libya. Of course the activity of the UNHCR is subjected to the will of the government which is subjected to the will of the militias. So, they don’t let them evacuate many people. Just a few thousand out of 60000 who are the refugees. Those who really deserve refugee status and therefore a place in the world to be.

Michelangelo: For all the others, very hopeless. It’s like we are just pushing them to risk life on the rubber boat. Not as a way to come to Europe, but simply as a way to leave Libya.

Colin: How does somebody get repatriated? It doesn’t sound like you can just decide to leave if you are in a detention center. So, what’s that process from …?

Michelangelo: When it happens, sometimes the IOM could even visit the detention center asking if anybody wanted to go home and it happened that they repatriated people taking them out from the detention centers. Of course, we’re talking about the official detention centers. But sometimes those who are outside the detention centers, they have the chance to contact or even to go to the office of the IOM. They simply registered. Sometimes even their own embassies in Tripoli can help. So, they have a list if names and this is a special program. They don’t pay for these flights provided by the IOM just as emergency flights. So, they have the right to get a flight.

Michelangelo: Unfortunately, as I said, number of those who are asking to go back is more than the flights which are offered therefore there are cases of corruption. So, the flights should be free, but if they don’t pay the worker in their own embassy, they don’t get the flight or they can wait even a year before being repatriated. I tried all my best honestly to highlight the story here in Europe because here in Europe it’s basically not possible to tell the story that people… That there are at least some people in Libya who want to go home because they only stuck in the idea that they just want to come to Europe or better to die.

Michelangelo: It’s not like that for thousands and thousands of people that were just abandoned in Libya while it would have been easy to rescue them from the country and taken back home.

Colin: It seems to me that this is part of the racism in Europe around migrants is the idea that coming to Italy would be still appealing and that wherever somebody is coming from is so dreadful that there’s a willingness to take these risks to potentially be enslaved, this kind of thing. So, you’re starting to get that story that it’s much more complex than that?

Michelangelo: Well, you’re perfectly right, but as I mentioned, when I moved back to Italy two days ago, I found that the debate here in Italy was pretty different compared to the one I was used when I was still in the country because the society here in Italy is much polarized. On one side we have the right parties and they want to close the borders, they would even sink the migrants in the middle of the sea, but on the other side there is also another polarized group of people who think to support the migrants by rescuing them in the sea. But surprisingly, I have to say that I noticed how much these rhetoric we can say is not able to describe what is the real situation in Libya and therefore is not able to offer real solutions for those in Libya.

Michelangelo: As I said, in the last year, just one migrant on 140 from Libya could reach Europe. So, while I start with suspecting that when we focus only on those who are rescued in the middle of the seas, we not to put our nose in Libya, not to know what is happening in Libya, not to know what should be necessary to do concretely in order to save all those who are in Libya, but I don’t know. You know, anytime when in a debate, the two parts are much polarized, it’s very difficult to make any kind of debate. So, these NGOs who are rescuing people in the sea, they used to say, “We must be in the sea to rescue them and not to leave anybody behind.” But the numbers say completely another story.

Michelangelo: So, it’s very difficult nowadays. Of course, it’s very challenging for me as a director to try to tell a story that seemingly nobody wants to hear and so let’s see what we’ll come.

Colin: You led me right to the next question I wanted to ask which is to go back to the technique of telling this fraught and often marginalized stories. You’re getting… It sounds like initially maybe some text messages or some voicemail, voice recordings. Eventually, pictures started trickling out in maybe low resolution, cell phone video. You’re a filmmaker, how are you taking this incredibly difficult story from all these fragments and try to turn them into the documentary you’re working on?

Michelangelo: Well, the documentary is made also by the videos I received from Libya of course and I said sometimes the people speak and I had to blur their face, but sometimes for example I have some videos who were recorded by some who are outside Libya currently. So, in this case, I will be able to publish even their own face because I have the permission to do that. Otherwise, there used to be the reporters. They just open the phone and they record whatever is happening around them. This was made not only by migrants, but also by Libyans. Just to show me how things really work over there.

Michelangelo: It seems absolute, but we received even videos footages from inside the detention centers made by migrants in these places I describe. That’s why I can describe them very well because I have many videos of them in this big compounds, sitting on the floor and talking to each other with a lot of voices, the noise coming from the background. So, these are the pictures and very interesting. Well, of course interesting in a way are the videos made by the criminals because in that case we have the point of view of the criminals and me as I director when I decided to use these footages, I have to think that the point of view is the point of the view of the criminal and I have to think why the criminal is doing that video in that moment.

Michelangelo: I have to try to explain what is the situation because otherwise I would consider them almost pornography because to see a man being tortured is not something you can entertain with. So, for example I used to show just a few seconds of the scene and then cut the video and continue with the audio because I think that what the criminals are saying to the migrants and the torture is more important than the footage itself.

Colin: Is it a film by Michealngelo Severini or does it end up becoming a film by all of the people who are living there? So then, how do you navigate the decisions you have to make as a director?

Michelangelo: So, the movie as I said is based on the real stories and on the real messages that were sent to me from Libya both when they’re videos or when they’re just both messages. I always repeat that in this case we are in the phase of self narration. Now we’re talking about doing the movie, but since two years now I’m running also the radio programs. So, what I’m doing is to let the migrants describe themselves and to narrate themselves which is the situation, their own story which is something I have to say quite unique at the moment. But at the same time, the movie is a movie made by me in the sense that I even didn’t try to represent themselves. This is the movie they will do by themselves when they will have the idea or the time or the will or the chance to collect enough videos. They will do their own movie.

Michelangelo: I can’t forget that I’m Italian and I have this point of view. So, I prefer to have a character in the movie and to tell the story of the reaction of this European guy in front of these stories, in front of these voice messages, in front of these videos because… Otherwise, I was afraid to make a video which is so unbelievable in a way for what you hear, for what you see that the watcher can consider something bad, of course something that should not happen, but so far away.

Michelangelo: But by showing the reaction of a simple European citizen which has the character inside documentary, I want to show the fact that we are inside the story. We don’t belong to a different story. We are part of the story. We are responsible for what is happening and it is absolutely normal that some people who has been tortured in a country which is just on the other side of the sea from Italy try to connect with me through the internet in 2020. It’s something which is what should be normal currently and I want also to show that it’s impossible that somebody could think that what was happening in Libya would have been hidden inside the country.

Michelangelo: Nowadays with the internet, nothing can happen in the world that cannot be shown to the rest of the world. So, I think it was important to represent also my point of view and the reaction that we as Europeans have to produce after being aware of this story.

Colin: So, when we were first talking, getting to know each other, I asked you a question and your response to it stuck with me. I don’t know if I’m quite representing it right, but I asked you about your background and what motivated you to take on this very difficult story. I was interested in your biography, in your background as an artist and a musician and your response at the time was really interesting. You basically said, nope. The thing is, I’m just being a citizen and so I have to do this. I wonder if you can talk more about your idea of citizenship and what kinds of responsibilities you feel that that means you have to carry out?

Michelangelo: Yeah. Well, of course anybody is different. I always felt the idea to be a citizen as in a way as being responsible of what is happening around me in my society. But at a certain point of my life, when I was pretty young I realized that it’s more interesting even what is happening outside my society because from Europe for example, I used to travel when I was studying in the university. Those times I was traveling in the former Yugoslavia just out from the war. Then I traveled north Africa and the middle east. I have lived six years in Turkey. So, I was always in understanding what was happening outside my own society to see which are the connections and to see if our lifestyle is still acceptable. I mean, is still sustainable with life and with respect of the dignity of the life of other people.

Michelangelo: Unfortunately, I was always disappointed anytime I made the struggle and that’s why I used to perceive my work like this especially when I’m a filmmaker because… So, I think my work is a story, but I also know that while telling stories, we can show some part of the reality which are normally hidden. For example, I don’t consider myself a journalist. So, I’m still storyteller, but I like to tell stories which in a way describe the relation between this in and out, this us and them. Because at the same time, here it’s true we can say we are Europeans and those are Africans or we can say we are white, they are blacks or we can say we are Christians, we are Muslims, but at the same time we share the same Mediterranean sea.

Michelangelo: But for me as an Italian, it’s something very important. So, I cannot avoid to consider those people in north Africa as brothers because we in a way belong to the same sea side, through the same culture, through the same food, through the same lifestyle also. History also put us together a lot of times. I cannot accept that we are building walls and defend our interests on the skin of our brothers just a few sea miles away from here.

Colin: There’s a tendency that I think some people feel to take hopeless stories like the one you’re telling and feel hopeless and feel as a result powerless, disengaged. This is so much bigger than me. What could I possibly do? Do you have a counter point to that? What do you want people to do with the film when they see it and afterwards?

Michelangelo: Well, I can tell you that the movie in a way ends with a big feeling of frustration, but in fact I don’t think that my duty is the one to change things because I’m just a filmmaker. But of course I can show a different picture. I can try to make people understand which is the correct picture about the situation, which are the real actors in the game, what are their role, who is doing what. Then once I can provide a different picture to the people, then it’s something that should raise in the consciousness of the people. I’m not a guru, I don’t think I can move or change the mind of the people just because I don’t know of what? Of my charisma or what?

Michelangelo: I can just tell a different story. I can just provide correct information to the people and then, I used to say that I consider myself happy when I succeed in making people think twice. In this case, maybe I’m even asking more that thing twice because I have a chance to really tell completely different story. More than this, I cannot do and so anytime I feel frustrated, I go back thinking that again, I’m a limited man. So, I’m not able of course to change the history and I’m just going to do my best.

Colin: Where are you at in the film and what are the next steps?

Michelangelo: So, the movie is finished. We just applied to a few festivals. If I may mention, we applied also to the Toronto Film Festival and so we are waiting for the answer that should come in a few weeks. I’m feeling very confident because I think the movie finally was a very good job by all those who supported me and all those who worked with me both in Italy and in Tunisia where also the movie was shot talking about our shooting. So, of course then we have the material that was made by the migrants from Libya. I just hope, I really hope that there will be no political influence to prevent the movie to be screened in the festivals. I think it won’t happen in Canada, but of course we applied also to different countries.

Michelangelo: Honestly, I have to say that the positions were explained in the movie nowadays currently in Italy are out of the media completely because in this situation, in this war fought in Libya, officially the Italian government is in the position of the government in Tripoli. So, it’s not possible to criticize. Last week the Italian government renewed the agreement with the government in Tripoli saying that with this money, the legal institutions will improve the conditions of the migrants in Libya, but I had a program on the radio yesterday from a guy talking from detention centers and he said we don’t see anybody from the UNHCR since three months. So, how can they improve situations if they even don’t come here?

Michelangelo: So, unfortunately these stories are quite uncomfortable for the European governments. So, I guess it won’t be easy to promote this movie in Europe and in Italy.

Colin: I really hope we’ll have the chance to see the film here in Toronto and I hope everything goes well there. You’re clearly not done with this story. You mentioned to me before the beginning of this that you were off to Tunisia shortly to continue. So, what’s next?

Michelangelo: Well, the next, honestly I’m very curious to see what happens with the movie because I cannot hide the … We are hopeful that this could be a tool to open some spaces in the debate. Also because this is a difficult to understand if you don’t see it as a wall. Sometimes when you have maybe radio programs, yes people can follow or articles, but they always catch some path and just once you are able to have the whole picture then you realize as I was saying, how to relocate the different actors on the playground, play table.

Michelangelo: So, we’re confident that this movie could help to highlight all this story about the project exodus and honestly there are a couple of more projects coming out after the movie which is a book that we published in Italy. Also, we are about to produce a TV series always On the story, but more than what I can do or what I can publish, I hope that this movie will produce an effect at least in the debate, in the public debate. So, it’s time that people in Europe realized what has been happening in Libya in the last years.

Kaveh: You can find out more about the project on its Facebook page at Exodus – escape from Libya, on Vimeo at vimeo.com/exoduslibya or on SoundCloud at https://soundcloud.com/exodus-escapefromlibya.

Kaveh: It was Episode 13, trapped in Libya.

We want to thank Michelangelo for accepting our invitation and Colin for hosting this episode.

Marshall Bureau composed all tracks in this episode.

We appreciate the continuous support of the Inclusive Design Research Centre at OCAD University.

Please check out our website, quantization.ca, for more episodes and full transcripts, and come back for upcoming episodes.

[Music]