Alex Mayhew and Colin Clark on Classical Art and Augmentation!

Hi, we are Arezoo Talebzadeh and Kaveh Ashourinia, and this is our podcast on inclusion.

[Music]

Quantization is an independent project with the support of the Inclusive Design Research Centre at OCAD University.

[Music: Quantization (Theme-Guitars)]

Arezoo Talebzadeh: Hello and welcome to the ninth episode of Quantization.

Colin Clark: Are they okay, the levels? Am I fine where I’m sitting and everything? Yeah? Yeah? Okay, well.

Alex Mayhew: Do we need to talk a little bit more into the microphone?

Colin Clark: He’s giving me thumbs up and says no, so I think we’re-

Alex Mayhew: Okay.

Colin Clark: We’re good, and I think he’s saying we can get started.

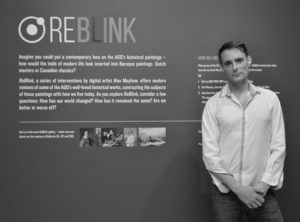

Kaveh: Between July 2017 and April 2018, Art Gallery of Ontario exhibited ReBlink a visual experience of augmented reality intervention of a few classical paintings.

Arezoo: This exhibition raised questions about augmented reality in the art domain and intellectual property also inclusion in art exhibitions. How classical pieces can be translated, represented or combined with new technologies? Is there a way in which we can make classical art more accessible?

Arezoo: To find out more, we invited Alex Mayhew, the creator of ReBlink and Colin Clark, artist and researcher to our studio to talk about these questions.

Arezoo: We also have a short announcement at the end of this episode.

Colin Clark: Well, should we start with introductions?

Alex Mayhew: Yeah.

Colin Clark: Kaveh says yeah, too.

Alex Mayhew: Okay.

Colin Clark: I’ll go first. Then you can go.

Alex Mayhew: Okay.

Colin Clark: Hi, I’m Colin Clark. I’m an artist and an inclusive design researcher here at OCAD University in Toronto. My research work is around multiple modes of representation, so how you weave together different forms of perception, sound, vision, etc. I do a lot of work with co-designs, moving past the sort of static modeling of people as individual attributes or marketing research or bits and pieces, and rather ways that people can get involved in the design process as actual participants, as designers themselves. We look a lot at ways to get past the focus group or the workshop and get people who are going to use the software we build into the design process as full creative contributors.

Colin Clark: My art practice is both as a filmmaker or video artist and musician. I develop a lot of homemade video processing and sound processing tools, mostly using the web, in part because of an interest in the ways in which creators interact with each other at a material level. If I write a piece of software, what are the options for me to give it to you? I could opensource it and you could fork it and change it, but are there ways in which we can both create artifacts that are somehow linked or connected together so that we don’t all have to separate in terms of how we make things.

Kaveh: And Alex Mayhew!

Alex Mayhew: I’m an artist and a designer. Recently, well, a year or so ago, we started a company called Impossible Things. We’re a bunch of artists and designers, and actually we all have fine art degrees, but we do a number of projects, whether they’re art-based or design-based, and the idea is that our art practice informs our design work and our design work informs our art practice. We specialize in augmented reality, mixed reality, but with a particular specialization in augmented reality. We also have backgrounds in transmedia and game making, working in industry, doing commercial projects, but also doing a lot of artistic projects. Ones that spring to mind would be a project I did for Peter Gabriel, which shows Ceremony of Innocence a long time ago, which won a lot of artistic critical acclaim. There was another project I did for the Royal Shakespeare Company and MIT, which was basically visualizing and working out interactive concepts for a game version of The Tempest.

Alex Mayhew: For quite a long time I was in this kind of no-man’s land of being between game and arts, and for a while it was a no-man’s land. There were very few people in that area, and there was very little activity or work, but the projects you picked up were very interesting. Now, Impossible Things seems to be under quite a lot of demand right now.

Colin: It’s not a no-man’s land anymore, it sounds like.

Alex: No. No. We just have to show the AGO, which is a show I initially started to get off the ground a couple of years ago, which is, I think, what we’re going to be talking about today.

Arezoo: This is season one called signal, episode nine Classical Art and Augmentation!

Alex: Shall I explain a little bit about what the show is?

Colin: Yeah. I’d be curious to hear what [ReBlink inaudible 00:03:54]. I’ve been thinking on this podcast that we’re in a completely different medium from one you work in. Here we’re in a room with only sound.

Alex: It’s nice, isn’t it. Lack of computers.

Colin: It’s nice. No computers. It’s quiet. Maybe think about ways in which you could describe what ReBlink is and does for those who are listening and can’t see it right now. How can we evoke that in some distant presence.

Alex: Sure. Yes, it’s definitely challenging talking about it, because it’s such a visual experience. Essentially what we have, when you walk into a gallery you see a number of different paintings, and ReBlink focuses itself on all the works of art. We’re very much working in the convention of arts intervention, a little bit like Kent Monkman may do, so we take an existing work of art, and then we respond to it with another work of art that directly references it but also kind of creates commentary. Most intervention works of art are usually displayed in the same gallery, sometimes hopefully in the same room, but often the two works of art may eventually get separated and they may even live in different countries. What we’re doing is creating an experience where they’ll always be linked together and they’re designed to be actually viewed together in the same space, and we do that using technology that probably most people have heard of called augmented reality. The most popular applications that people would have heard of would be things like Snapchat or Pokemon Go. Ours is slightly different to those, very different to those.

Colin: Different how?

Alex: Different in the … I would say Snapchat and Pokemon Go is probably a little bit like fast food. A lot of fun, tasty, not very nourishing necessarily. What we’re trying to do is actually create an artistic experience using the technology to create an artistic experience.

Alex: What happens is you walk into the gallery. You see the original painting. You hold up your device, and this could be a tablet or a smartphone, hopefully you’re got your sound turned on, because sound is an important part of it, and as you lift up your device you see the original painting, but then you see the screen crackle as a new reality seeps in onto your device, and suddenly the painting that you’re looking at through the camera has changed somehow. What we’re doing really is focusing on the theme of looking back at the past with our present day lens.

Colin: Right.

Alex: We are creating modern day references that somehow link back into the past. We also are turning some of these environments into … the flat 2D painting experience, we’re turning some of them into 3D experiences, so you can actually see around corners or imagine that frame isn’t a frame to a painting, but now it’s a window frame that you can actually look around corners and see what’s lurking on the left and right side.

Colin: Yeah.

Alex: We’re trying to use those spaces as part of the commentary, too, so we hide little things in those spaces.

Colin: Right.

Alex: Was that clear? Because it’s still very hard to explain.

Colin: Yeah. I think we should go through and maybe try and describe some of the pieces at some point, but it struck me when Kaveh and I went to see it that the viewer’s perspective becomes the center point to the work. We always have a perspective and the painting is always going to frame the subject in some way, but then your work, by virtue of the fact that you have a second frame that you as the viewer hold up to the piece, and then, again, that 3D space that you’ve brought into that second frame so as the viewer moves they get to see a different angle or some depth at the base that they wouldn’t have seen.

Alex: Yeah, that’s very nicely described. Sometimes I describe it to people that … What is it? What have we created? Is it the thing in itself, or is it the original … Is it two works of art? Really I would say that it’s designed to work holistically, so the original work of art is a very important part of the experience, and the remix, or the intervention, is a very important part of the experience, but they need each other to work. Really the power and the tension comes between the relationship between the two, that kind of invisible space in between.

Colin: Right.

Alex: It’s really those contrasting realities. I think there’s something about augmented reality that can really help us experience the commentary in a way that somehow feels very, very real, because we can literally explore that space.

Colin: Mm-hmm (affirmative). What does it mean to augment reality? I hear this term and I think, okay!

Arezoo: Per Stuart Wood and Rachel McCrindle in their paper “Augmented reality discovery and information system for people with memory loss” AR merges computer-generated objects with real-world concepts in order to provide additional information to enhance a person’s perception of the real world.

Augmented reality is a technology whereby a user’s view or vision of the real world is enhanced or augmented with additional information generated from a computer model. The enhancement may take the form of labels, 3D rendered models, or shading modifications.

Colin: So reality suggests maybe that it’s photographic or video-based, and maybe it’s situated in your present time and space, but then what does it mean to augment it?

Alex: Well, I think there’s a lot of debate about what reality actually is. I’m not sure if I’d define it as you’ve defined it. But, yeah, that would be an endless debate. To augment it we need to look up the word augment in the dictionary, but I kind of think of it as a layered reality, so we’re simply laying, in the case of what we’re doing, we’re laying on a digital layer on top of reality in order to change it or to alter it in some way, all to help us understand it. I think in a way that’s what we’re doing with ReBlink because, in terms of helping us understand the original works, that was part of the motivation of why the project happened.

Alex: There were two motivations. One was this was a creative artistic opportunity to create a new kind of storytelling or new kind of artistic experience, but the other motivation was to get people to stop and slow down and relate to the original works, because as I was spending a lot of time in the gallery before the project happened, I would notice people walk through the gallery, glance at paintings for a moment and just walk past, or occasionally they’d get their cellphone out, take a picture, not even look at the painting, and then walk past. I think part of the problem is, especially with some of these older paintings, is there’s very little in our own lives that we can relate to those paintings. Especially with younger audiences it’s like, “Well, that painting’s got nothing to do with me.” What we’re actually doing with ReBlink is pointing out the similarities with today, but also pointing out the differences, highlighting those things and actually using that as a way to help other people understand the relationship between now and then as a means of understanding the past by virtue of contrast or similarity.

Colin: I’ve read interviews that you’ve done for the project in the past, and you’ve emphasized, I think in every case, this experience you had in Toronto visiting the AGO as a kind of respite, a place to go and think and absorb the knowledge that these artworks that you were looking at had, and you sat on the bench and you spent time with the work, maybe attending to it, maybe not, ignoring it, whatever, daydreaming, but that what you saw were people ghosting by the works, as you said, just spending a few seconds or taking a picture and moving on. That to me, there’s a kind of interesting, and I don’t know if you agree with the interpretation, but there’s a sense of loss in the piece to me that’s doubled in an interesting way. It’s not a utopian piece by any means. The imagery and the transformation of the original works tends to be a little towards the darker side, maybe a little cynical.

Alex: I’m glad you take it that way, because some people think it’s a bit flippant, and actually it’s not. The irony is that we’re using the very technology that’s partly responsible for our-

Colin: Right. That’s what I wanted to get at.

Alex: Quick consumption of media and all of these devices, and the Instagram generation, we consume images and media so quickly, and I think that’s partly to blame for our lack of attention in art galleries and our lack of ability to be able to connect, and we wanted to try and turn it on its head somehow and to use the very technology that’s party responsible for that negative thing, as I’m trying to describe it, and actually use it as a way to get people to stop, slow down, and explore. I think that there’s humor in some of the pieces combined with cynicism. The perfect one would be the [Franz Howe 00:13:39] portrait.

Colin: Do you want to describe that one?

Alex: Yeah, there’s just this dude in a painting from the 16th century, just looking out. He always looked a bit cheeky to me. A very simple, beautiful painting, and especially with that one I’d see a lot of people just walk up, snap a picture, and then walk a way. I thought, “Well, how would they like that?” So what we’ve done is we’ve turned the tables, and I call that piece The Painting’s Revenge. It’s very simple. You hold up your device and then he’s holding his device up at you, and he’s taking pictures of you. No matter where you go in the gallery, he’s just following with his arm and snapping away at you. We have some contemporary music played with baroque instrumentation. We have Hotline Bling by Drake.

Colin: Hotline Bling, right away you hear this and you think, “Ah, I know what this is.”

Alex: Did you recognize it?

Colin: Right away, yeah. It was amazing.

Alex: Played on a harpsichord. We got it played on a harpsichord specially.

Colin: Yeah, that was a great touch. In fact-

Alex: We don’t know what Drake thinks of it. I don’t know if he’s-

Colin: He should get in touch. When Kaveh and I were first going to go and see the show, you emailed me and you said, “Make sure you have the right equipment. Give me a call and make sure you have the right equipment.” There was a sense I got that there’s a way in which you want the work to be experienced and appreciated, and part of that maybe is the connection between the visuals and the sound?

Alex: Yeah, I’m a fussy bastard, and I try and force that on as many people, whether it’s making coffee or consuming art.

Colin: Does technology make you more vulnerable to consuming art in ways that aren’t how you intended? You, the artist, intended?

Alex: Yeah, definitely. With a painting you can’t really go that wrong. You could hang it in a completely inappropriate place.

Colin: Like a dark room.

Alex: In a dark room or in a toilet. It would have a different meaning hung on a palace wall. We know the way that you place paintings will have a great influence on how you perceive them or how it’s framed. With digital it gets a lot more complicated because we don’t know what size devices they have. In the gallery they feel like people should turn down their sound, where actually sound is a really important part of this, and we want people to turn their sound up, but still to wear headphones, because otherwise it would be like watching a movie with the sound down. The soundscapes are very important in there. There’s a lot of subtleties in the sound that we went through a lot of pain to implement. Hector Santino, who is a great technical lead, but also an artist himself, is very keen to put in as much sense of three dimensional sound and create a sense of proximity as you move closer and further away from the paintings.

Alex: Of course, the other thing is when you’re looking at a painting, generally you might just stand in front of it, maybe take a couple steps back, a couple of steps forward, but with ReBlink, partly because we have a window that you can look through into another world, it’s designed for you to explore a lot more, so to look at things from different angles or to get right up close, but look at the edge of the painting, because there’s things that you’ll see that you won’t see otherwise, but also we have elements of the augmented reality that react to the proximity and the location of the user, thus hopefully creating the connection between the visitor and the painting. For example, this [Krakoff 00:17:45] piece shows a beautiful pristine country landscape. I wanted to do a piece on all of the dodgy things that are happening with the environment ranging from polluted water that can’t really be drunk anymore to demolition of beautiful village locations and the pipeline.

Alex: All of that is in the intervention, but there is also a man standing in a hazmat suit right in front of the painting. He is supposed to represent the kind of authority figure of the big corporation and doesn’t want you to get too close to the action of these buildings being demolished and as the pipeline is being installed. He will actually look at you wherever you are in the gallery. He’ll follow you around with his eyes, and as you get closer he’ll lift up his walkie-talkie and he’ll, “They’re getting closer, over,” and talk about you as you move closer, and he’ll respond as you move further away and closer still. We’re creating that direct connection as a direct relationship. All of those things are completely out of the norm of a conventional viewing of a painting, I guess.

Colin: Again, going back to this issue of this doubling of loss, so the stories tell something specifically about loss, but then the story is told through the agent of that loss, the cellphone, right? So if part of what’s missing culturally is the time, the attention, the impact of technology and modernity on the environment, then it’s this very window that the viewer is looking through that is what you’re speaking to. What is the catalyst? You could think about it in terms of a genre of dystopic video games or cyberpunk movies or things like that, but beyond the traditions that maybe it’s part of, what do you want somebody to take away from ReBlink, and maybe what kind of a relation back to the source, the original painting? Do you think that the phone gives them … If the painting was being ignored before, and now you’re intervening on the process of seeing it, then what happens?

Alex: I’m not sure if I understand the question.

Colin: I guess I’m getting … Do you think it works? Do you think people notice the painting more or do they notice your intervention?

Alex: Oh, I see.

Colin: Or does that matter?

Alex: I think some people get more carried away with the digital inventions and might not look at the paintings, but we did notice right from the beginning when we did the proof of concept is that people were looking at the paintings. They were comparing the two.

Colin: Right.

Alex: I think that’s … Again, it’s the tension in between, it’s the magical relationship between the two things, and it wouldn’t have the impact if it was purely the remix. It would have an impact, but it wouldn’t have the impact, because how things have changed from the original to the remix is the power of the piece. Of course, there’s an initial seduction with the bling, if you like, with the technology and the newness of the technology, but this really goes beyond any kind of gimmick. It wasn’t done for gimmick sake. It was really done because initially it was an interesting way to tell stories, and a new way to tell stories, and the fact that actually this could solve a problem for museums and galleries and be a powerful tool for an engagement and outreach was kind of a secondary thing, but I think was also partly the incentive for the AGO wanting to move ahead with it.

Colin: Right. This problem for galleries and museums is an interesting one. Maybe talk a little bit first about how you approached or started working with the AGO on this.

Alex: Sure. I’d actually already had a relationship with them because I did a previous project as a designer, which was a treasure hunt called Time Tremors, and we had some AR pieces in there, but it was really scratching the surface of the potential of the medium, but it was still very compelling for kids. That gave me the idea to … And sitting there looking at these older pieces thinking how different they were to … Well, okay. It comes down to one piece, and it comes down to drawing lots, the wide panoramic beautiful-

Colin: My favorite-

Alex: Yeah.

Colin: Intervention you did in the [crosstalk 00:22:57].

Alex: Okay. That was the trigger piece because that was the one I used to sit in front of as I was having a bit of a breakdown because of my chaotic city life and work time. It was a hard time. It was just so peaceful, and that’s when everything came together in my mind. Okay, well, my life’s not peaceful at that, so I’m connecting with this painting because of the contrast, so let’s do a project that we can help other people connect with it, because all these people are walking past.

Alex: There is also … you described it as a kind of cynical dystopian exhibition, which I’m actually really happy to hear you say that, because I think some people say, “Oh, they’re just having fun,” and actually it’s doing both and I’m not doing a Trump, in the sense that augmented reality in that way. He augments his reality all of the time. I’m not doing a Trump in the sense that looking back at the past wasn’t everything great back then and now we’re all screwed. Some of the pieces I think point out the good things about now, and there are some positive directions that we’ve gone in, and actually, despite all the horrible things that are going on in the world, I’m actually an optimist and we just have to look at the history of humankind to realize that we are increasingly living in the most peaceful times that humans have ever lived in despite all of the crap that’s going on.

Colin: Interesting.

Alex: Sorry, I’m slightly [crosstalk 00:24:47].

Colin: No, no. I think that was exactly the question I asked previously as well.

Alex: Trump is an interesting one, because what he does is he lies and he augments his reality, and what I’m trying to do is get to maybe a greater truth or an updated truth of a previous reality. This is how it was back then, and this is how it is now.

Colin: Does it ask any questions about how things could be?

Alex: Not consciously, but that would be great. That’s the next project.

Colin: There you go.

Alex: Yeah. I’d like to do something that would look into the future or speculate on the future. This is what will happen if we don’t change our ways or if we carry on with the way we’re going. Yeah, that’s another project.

Colin: Actually, let’s go-

Alex: Do you want to describe a couple more of the pieces?

Colin: I suppose. Yeah, Kaveh, I don’t know if you have any opinions, but I have a sense that you don’t want to take away what somebody might discover in the gallery, but on the other hand if they can’t envision what the pieces look like.

Alex: I’ll give you one more description, which would be … because I think we’ve only really described the selfie photo guy.

Colin: Yeah.

Alex: I can talk about the evisceration of a roebuck, part of the European collection, and it came to my attention quite a long time ago, way before this project, because I was just walking along in the gallery and looking for paintings to go into this thing we were doing for kids, this treasure hunt, and I saw this painting of this couple at this table preparing this feast, and on the table were these dead animals, including this huge deer, this roebuck, and it looks at you directly in the eye, and the man has got his hands over the deer and he’s essentially opening up its stomach, and you see these guts and blood and everything. Really my first reaction was that’s really quite disgusting and is that appropriate? I had kids in mind, too.

Colin: It’s usually symbolically loaded, if I understand. All of these cues that this was a wealthy couple at a particular place and time, there’s tons of stuff around them in addition to the [crosstalk 00:27:16].

Alex: Yeah, it was a bit of a status symbol, these two.

Colin: Right.

Alex: My immediate reaction was really should I have this hung at a height that kids can see it and should this even be on display, and it was a very narrow-minded reaction that I had. Then it came to thinking of some ideas for ReBlink and some interventions and that one stuck in my mind. I had slowly realized that it wasn’t disgusting at all. It was very direct. Animals have to die and go through pain in order for us to eat them. A lot of people I know can’t eat meat unless it looks like it’s not an animal. If it’s got an eyeball in, it’s kind of off putting or even liver. So much of our food these days is processed, so the intervention essentially reflects that.

Alex: When we lift up the device, the reality comes in, the new reality crackles in, and we see the same couple and he’s leaning over the deer, except now it’s not a deer. It’s a pile of bags, plastic shopping bags, in the shape of a deer. So you have instead of guts hanging out, you now have processed meat hanging out, and you even have sausages making the shape of the legs, reflecting the shape of the original roebuck, and the antlers and ears of the roebuck are now reflected in the shape of the plastic bags, and the lobster that was previously in the shot is now exactly the same lobster, but now it’s on the front of little cans, and the fruit is all now packaged with extra sugar. I went to find the worse possible representation of modern day equivalents of these foods. It’s a sad case that everything is so very processed, and I think as a result we’re so distant to the origins of where everything comes from.

Colin: Yeah. There’s a kind of abstraction that it attests to that that distance between where food comes from … There’s still all of the plenty, right? There’s no lack-

Alex: There’s more plenty.

Colin: Yeah, there’s more.

Alex: There’s being more waste.

Colin: And yet it’s less real.

Alex: All that plastic, too. Every time I go in there they always offer me bags. Well, just give me bags. Yeah. It’s kind of depressing. I kind of see that although it’s a cynical piece, I see it as a positive piece, because it hopefully gets people to think a little bit about not so much waste, but how far we’ve evolved separated from … I can’t even put it into words. I think the image puts it into better words than I can.

Colin: One of the reasons, again I’m interested in descriptions of the work, is because of the gap between us and our listeners, and then maybe the difference that people have and what they can do and how they perceive going to the gallery. Beyond describing the pieces, I’m curious if we could talk a little bit how one might open up access to ReBlink speculatively for people who maybe can’t see it in the same way that you or I can.

Alex: Yeah, sure. Well, we are working on a version of ReBlink that will in theory allow anyone in the world to experience it, because currently you have to be in Toronto, Ontario at specific dates. The show has been extended four months, which is good-

Colin: Congratulations.

Alex: But it still doesn’t give everyone the chance to go there and you always have to pay to get in. There is an issue to do with accessibility, and we want to get this out so as many people can see it as possible, especially in remote communities of Ontario and schools and so forth. We know that although it’s been a hit with older generations and middle ages, I don’t know if there’s a term for them, and millennials, it was particularly a hit with kids. We had a lot of school groups and teachers have been in touch who have gone wild over it. I had this one email about this woman who took 300 of her students especially to see ReBlink, and she’d never heard them talk about art in that way.

Colin: Interesting.

Alex: They were getting really into the commentary between then and now, and that was such a delight to hear. We want to try to make this available for all, so we are creating a version where you can make the original painting appear in your living room or in a schoolroom or anywhere. I did a version where I took Evisceration of a Roebuck, The Feast we call it, and we did that in metro, which was the original source material, and that looked amazing in there.

Colin: Metro the grocery store?

Alex: Yeah. They weren’t very happy with me, but that’s art. With this, the idea is you can hang the painting on your wall, you can place the painting in your room, and you can walk up to the painting and we’re sticking a kind of educational lens on there so it will give you a commentary depending on which parts of the painting you’re looking at. It knows which part of the painting you’re looking at. Maybe we’ll set challenges for students.

Alex: You can walk up to it just like you can any painting, and it really does mimic or echo the real viewing experience of looking at a painting. Because if you’re looking at paintings from the Van Gogh museum, the best thing you have are books and the printing quality is usually dodgy, or you might look it up on a webpage in a tiny little box, whereas when you’re looking at it on a tablet, it’s like it’s hanging in your room, and you can walk right up to it. You can even see the texture of the paint, the 3D’ness of the frame. Because we’re doing ReBlink in this case, you can actually get the intervention triggered, and all you do is simply shake the device and the interference comes up and the new reality seeps in, and you can now see this three dimensional space behind the frame and it’s completely masked, so you can walk around the frame and you’ll see the back of the frame, but if you look through the frame you see the three dimensional reality.

Alex: We’ll post a couple of videos up just to give that illustration of what I’m talking about. The other thing that you can do, which you can’t do at the AGO, is you can walk right up to the painting, because obviously at the AGO you don’t want people walking into million dollar paintings. It’s not a good idea, but also they would hit the wall as well, but in the case of this version of ReBlink, you can enter inside the painting. You can literally walk inside the room of some of the pieces and look around and even go around corners and discover new things. It’s kind of immersive augmented reality, a little bit like virtual reality, but it’s augmented and virtual at the same time.

Colin: Still taking in the space you’re in in some ways.

Alex: Exactly.

Colin: You still have to worry about not walking into a wall, but if you have the right space you can walk into the painting.

Alex: Exactly. It’s a little bit Alice Through the Looking Glass. It’s got that kind of feel to it.

Colin: That’s great.

Alex: Just walking from your own reality into another, and then you turn around and you can actually now see your reality that you left through the frame, but you’re looking back the other way. You’re actually inside the painting. So anyway, that’s what we’re working on. There’s a lot of work to do. We’re not quite sure how many we’ll be able to do in that super deluxe 3D, but we know that it does feel very impactful.

Colin: This history of access, it’s interesting because you immediately brought up the fact that we’re really talking about all kinds of dimensions to access. For somebody who can’t be here because they don’t live in Toronto, perhaps they can’t easily get out of their house for one reason or another, so you’ve got an option there, but under-

Alex: Even with the ReBlink show, this wasn’t particularly deliberate on our part, but we’re dealing with a different type of accessibility, because the whole world of art is shrouded in quite a lot of intimidating academic talk, and especially with older works of art. I was lucky enough to be invited on to Q with Tom Power, and he was saying to me after the broadcast that he used to hang around outside the AGO because he didn’t want to go in because he was intimidated by those old paintings. They somehow would scare him because they seemed intellectually intimidating in some way. He was dragged in to see ReBlink and his whole perception changed, because he realized, oh, that was just a different time. We’ve got a similar set of hangups now, or we just do things in slightly different ways and not only was he able to experience the original ReBlink paintings and not be intimated by them, but it actually, he said, changed his whole perception of old works of art. I think there’s something about ReBlink and the popular, having fun, the use of the technology becomes an educational engagement experience without it being overly didactic, and it can help people that wouldn’t otherwise appreciate old works of art appreciate them.

Colin: Mm-hmm (affirmative). There’s also a sense that it in some way personalizes the artwork, it brings it close to you. I’m thinking, for example, of the one in which you’re actually prompted by ReBlink to take a selfie with the characters in your intervention.

Alex: Yeah, you can stand there and it will trigger a different sequence. That’s kind of a viral piece. I don’t think that one is particularly successful. It’s okay, but the idea was that … Well, it’s one of two ways. There’s a married couple. They’re painted separately and I found it incredibly sad that they were hung so close to each other, but they were in separate realities. Now these people, we researched it. They loved each other, and there’s one thing that technology does do. When you point a device, people get together for the inevitable shot. We saw it as a way of reuniting this couple. The man would get up and join the woman and pose for that photograph, but the other thing that happens is if you’re standing in the middle, this piece gets a little bit more cynical.

Alex: If you’re standing in the middle, we have this technology that Hector coded that tells it someone’s standing there, and it triggers all of the ReBlink characters to come and pose with you, and you hear the, “Oh Canada,” because it’s Canada 150, and the boy is waving the flag and everyone is having fun. You take the picture and then the music screeches to a stop, the flag falls to the ground, and all the characters disappear. It’s a bit of a commentary on standing on ceremony or the superficiality of that camera opportunity moment, and as soon as the picture is taken, the smiles fold and realities change. Anyway, that was a means of inserting yourself in the picture and having that sent out to other people, but it didn’t quite work out.

Colin: Maybe I’ll tell you a story about my favorite visit to the AGO, and we’ll see where it goes, because there’s maybe some things related to ReBlink here, and with the big Jack Chambers Retrospective was in town. Jack Chambers is a Canadian artist from London, Ontario, who was a filmmaker, a photographer, and an absolutely incredible realist painter. I went with my friend, Geneson [Asunchion 00:40:42], who is blind and well known in the accessibility world in terms of looking at how to make technology more accessible for people with visual impairments, and my wife Darcy and my coworker Michele DeSouza here at the IDRC. The four of us went and had to go through a process of working with Geneson and describing the pieces as we stood in front of them what did we see.

Colin: Something really interesting happened, which was at the nexus between conversation, interpretation, and description. We’d stand in front of a new painting and someone would hazard a description, just a literal, “Oh, look. It’s a tree. It’s a big tree. There’s a beach scene nearby. The tree is really green and filled with radiant yellow sunlight,” and you’d sort of describe what you saw.

Alex: Objectively.

Colin: Objectively. Or maybe you’d say, “Oh, it looks like they’re unhappy in this scene. Something is happening here.” Then Geneson, absorbing different people’s perspectives and very quickly, especially once you got comfortable with what it meant to describe a work to somebody who had all the energy of being in front of it but couldn’t actually see it, then it became a kind of description network where one person had this observation and another person said, “Oh, but look at that.” There was a sense of a kind of discovery or surprise that I think is one thing that augmented reality does really well and that I saw in ReBlink a lot, which is that you’re kind of surprised. You discover something that isn’t there. It’s again in that between space, and you’re like, oh, this is wonderful.

Colin: Geneson would then interpret our descriptions, and he’d say, “Well, I think what you’re saying is that these people are like this,” or maybe it’d be a compositional description, so it’s like, “There’s a lot of triangles in here and it’s really bright colors,” so there’d become this other layer to the painting which was purely visual. These are gorgeous visual experiences, big in many cases, that you stand in front of and you just wonder at them, and yet there was this whole other network of descriptions and conversations and interpretations that made Jack Chambers’ work more interesting for all of us.

Alex: Yeah, because you were having to talk about it at a conscious level and then start drilling down into the meaning on the fly.

Colin: The meaning, how it felt to you.

Alex: I had a picture of you lying on the couch with a psychiatrist talking about your dreams and Freud is trying to make sense of your, or someone was trying to make sense of your dreams and help give them context or meaning.

Colin: Yeah, and then to interpret the dreams as they’re interpreted back to you, right, because Geneson would often basically say, “Okay, well, here’s what I think I’m hearing,” and then that would give you another perspective on the work.

Alex: It’s so interesting because we see ReBlink as one augmented experience, but we think there’s plenty of other experiences. We call them lenses, different types of lenses, which would be different types of experiences in front of whatever you’re standing in front of, in this case a painting, and one of the lenses that we really want to do at some point is something that can capture all of these conversations that otherwise get lost in the ether, and also let you contribute to them. You hear people talk about paintings in a very interesting way, and is there a way of somehow capturing that in a way without it turning into a bitch fest that you might have on YouTube.

Colin: The complaining or the didactics. It’s one experience to go stand in front of a painting with a gallery education person or even a curator who has their interpretation. My uncle is a curator at the Museum of History, and I was there recently and he gave us a wonderful tour with all of the history of how the exhibit was made and his view on the pieces and the art historical connections and these kinds of things. That’s one lens or mode that you want to work in, but maybe you just want to soak in the color. Maybe you want to think about how it made people feel over the years relative to how you feel these kind of things.

Alex: Do you want to hear what a six-year-old kid thinks of it?

Colin: Yeah.

Alex: Which is the opposite of a historian view.

Colin: Right.

Alex: Pure innocent perception.

Colin: We did a project quite a while ago now, it was when the iPhone and the first Android device were pretty new, where the collection was available to somebody with a personal device, but then they could look at the official description and interpretation of the work, they could add their own through audio recordings or text, and they would then make their own personal collections to take home with them. Teachers really liked this because it let the students wander through the gallery, but still have to be collecting or making note of things that they would then do in their work in the classroom. But the challenge of how do you make it fair and moderate it, and how do you try to draw the richness. Do you let people take photographic interpretations or record their own stories or make a video of the work?

Alex: I think AR has the ability to facilitate quite a few of those things, but you’re still going to have a lot of those challenges that you describe. We were looking at capturing those conversations, but the other things we were looking at were emotional responses to paintings, and actually have people literally lay out their emotions in visuals around the painting.

Colin: So they’d have like a toolkit of emotional symbols or something?

Alex: Yeah. We’re still working on it, and it’s a little bit on the back burner, but we have … If someone’s response to a painting is that they love it or it makes them feel these emotions, then we somehow convey those emotions in elements that they can leave in the space and AR, and then you can quickly swipe all of that off and see the next person’s emotional response, as well as the ability for them to write a little bit about why they feel the way they feel. We were working on things like glitter and sun rays and thunderclouds, quite beautiful imagery, but we haven’t quite had the chance to really test it.

Colin: In a sense, this might be people … If you’ve remixed the original artist, then there’s a layer in which people are remixing or augmenting or adding to that layer.

Alex: Oh, yeah. We’d love to have the ability of people to leave their own interpretations, their own responses.

Colin: Reminds me of a question I’ve been meaning to ask. Is there an ethics of remixing?

Alex: Well, yes, that’s a good question. You said earlier on about you allow people to get personal. Really all of these remixes or interventions, they’re actually my interpretations. They’re not everyone else’s interpretations. They’re my reinterpretations, and other people may not agree with what I’ve done, but they wouldn’t agree with what every single artist has done. I’m just working as an artist, but in response to another painting, so it is very much my perception and my picture of my response and other people may respond in completely different ways, which is why we’d like to facilitate that at some point.

Alex: In terms of ethics, there’s no written guidebook. All I can say is that for every single piece the responses came from a place of love. All of the artists have been dead for a significant amount of time.

Colin: Does that make a difference, whether they’re here or not?

Alex: Well, from a copyright perspective it does.

Colin: Right.

Alex: It’s easier to deal with dead artists that have been dead for 160 years or something. It’s a little bit weird walking around the gallery going, “I hope she or he has been dead for long enough.” You need them to be dead, because it makes things a lot easier. Then the copyright is not an issue. I think people would argue different ways. Some people would say, “Who are you to come and change a person’s work without their permission.” Well, actually I’m not changing it. I’m putting something next to it that is changed. You don’t need to look at it, but it’s an intervention that fits very much within the intervention mold. It does come from a place of love, so with every single piece I think you’ll agree they don’t look like cheap computer games. It’s really hard to create a deep aesthetic using 3D graphics and simulation of a painting. I think we’ve done a relatively decent job and we’ve put a lot of love and labor into getting those paintings at the highest possible aesthetic quality that we could.

Alex: I’d like to think that if I was a dead artist and people were forgetting about me or they were just walking past the painting, that there was someone there doing an intervention of my interventions that were actually getting people to stop, slow down, and look at my work again. I see it as though I’m … Well, I’m not really helping them out deliberately, but by default I’m hopefully getting people to stop and reconsider these works. For me, there’s so many more arguments to do it than not to do it, and I’m hoping that we’re giving longevity to these artists’ voices. Maybe that will happen one day. Maybe we’ll have the intervention of the intervention to the original painting, and it will just go on forever.

Colin: I guess one of the challenges of working with technology is how you keep works that are situated on particular devices and APIs and versions of operating systems alive.

Alex: That’s another bloody nightmare.

Colin: That’s pretty good to last a century.

Alex: Yeah, well someone was asking them about an old project I did, Ceremony of Innocence.

Colin: That’s the one with Peter Gabriel?

Alex: Yeah, and where can I get it from. You get it from Amazon. You can buy it for $100 American US dollars on Amazon.

Colin: That looked like it was maybe a shockwave or early flash project?

Alex: It was worse than that. It was director, and you can’t play it. You can buy it for $100 but you can’t play it on anything.

Colin: Yeah. Do you mind that that piece is gone, essentially?

Alex: I’ve got videos of it, and yes, but also it would just frustrate me, because although I think it stood the test of time quite well, it doesn’t look as original now as it was back then. It was very original back then, and now it feels that everything was done with a computer that has a tiny processor and everything had to fit onto a tiny little disk, and I think it worked really well considering what we managed to do for the technology, but now it just looks maybe not so much dated, but like if you made it now it could be so much better and so much richer. I’m kind of glad that it’s almost lost in time.

Colin: No artist is working alone. Are there video games that are influential or other artists? The reason I ask is because I think your work functions as much in the culture of extended gaming and cinema as it does in terms of a gallery or a painting environment. Is that interesting to you?

Alex: Yes, it’s interesting. I don’t know if it would be any one in particular influenced. There’s probably a number of different influences ranging from my dad, who is a very eccentric artist/philosopher/inventor, he just does lots of strange, creative things and doesn’t abide by any rules, not just with his art, in life. It’s about not rebelling, but just ignoring the rules, and that’s how you get different results partly. He used to also read us a lot of Alice in Wonderland, and I always thought that the ability of digital technology allowed you to do things that you just can’t do in reality. For example, step into another world or into a painting, into another reality. It’s always been a big influence on my work.

Alex: In terms of this particular show, I guess I have been influenced by some surrealists like Margarite; Duane Michaels, a photographer, beautiful, beautiful work. He’s really an artist that happens to take photographs, and he tells stories through sequential photographs, so within six frames he may tell a very beautiful elegant story. In a similar way, that’s how ReBlink functions. The first part of the story is the painting, and the second part of the story is the remix. At the time, gifs were getting very popular, and gifs have become a kind of realm of themselves, or a kind of genre. They’re not quite … They’re art pieces, but they don’t have to be art pieces. They can be animation, but they don’t have to be animation. They can be very dark and they can be very [inaudible 00:55:17]. I think those were also on my mind at the time.

Alex: Some of it can be very powerful. I would say criticism of ReBlink, well, it’s not really criticism, but they don’t have to be highly complex 3D environments. One of them is very simple. It’s the one with the kids watching TV and really I’ve just swapped one 2D image for another 2D image. It kind of animates, but I think the message and the power of the message isn’t necessarily dependent on highly technological solutions. For example, when you’re reading a book within four or five pages you could have gone through four or five different emotions. You can be really sad one moment and elated the next and then angry, and the technology, and it is technology, the technology of a book is very, very simple.

Colin: For sure.

Alex: Nowadays we tend to call things technology when they don’t quite work all of the time. Like a bike and a book, they work most of the time, so we don’t call them technology, whereas computers or this recording system that we have here doesn’t work all the time, so we call it technology. That’s my theory.

Colin: Well, thank you very much.

Alex: Anything else?

Colin: I’m good.

Alex: Sorry to talk so much.

Colin: No, no. It was great. Thank you very much!

Arezoo: It was the ninth episode of Quantization. We want to thank Alex and Colin for accepting our invitation, and all of you for listening to our podcast.

Special thanks to Marshal Bureau who composed all scores for Quantization!

Alex: You are really good; you should do this. You should do weekly podcast.

Colin: I leave the podcast thing to Kaveh, but I suggested that a theme of podcast on art and inclusion would be great.

Kaveh: That was our announcement. We teamed up with Colin to produce a series of episodes on Art and Inclusion. Tune in for more information.

For more episodes, more information and the full transcripts, please check out our website, quantization.ca and come back for upcoming episodes.

Tschüss!